In a review of the show The White Princess, the magazine Elle argues that the adaptation of Philippa Gregory’s work, which is but one in an entire franchise, sees “history become herstory”.

There have been five television/film Plantagenet and Tudor-era adaptations produced based on Gregory’s writing, a small figure considering she has written 15 books set during this period. This article will focus on just two of these novels, The White Queen and The White Princess, both of which have been made into television series. From which we will discuss three generations of historical women, Jacquetta of Luxembourg, Elizabeth Woodville and Elizabeth of York.

Perhaps the most notable claim prevalent in Gregory’s recount of the lives of these three Woodville women is that they descend from a long line of matriarchs competent in the work of the supernatural. Now, whilst Gregory makes sure to assert that her works are historical fiction, there remains some truth to her claims.

This article will analyse how Gregory uses the witchcraft accusations not merely as historical fact, but as a lens to grant the Woodville women secret political power and agency, exploring the tension between historical documentation and dramatic license, a tension which Variety argues is a flaw of the adaptation of the 2017 show The White Princess, where the plot is “lost in the weeds of historical detail and soapy reinterpretation”.

Janet McTeer as Jacquetta of Luxembourg and Rebecca Ferguson as Elizabeth Woodville in The White Queen

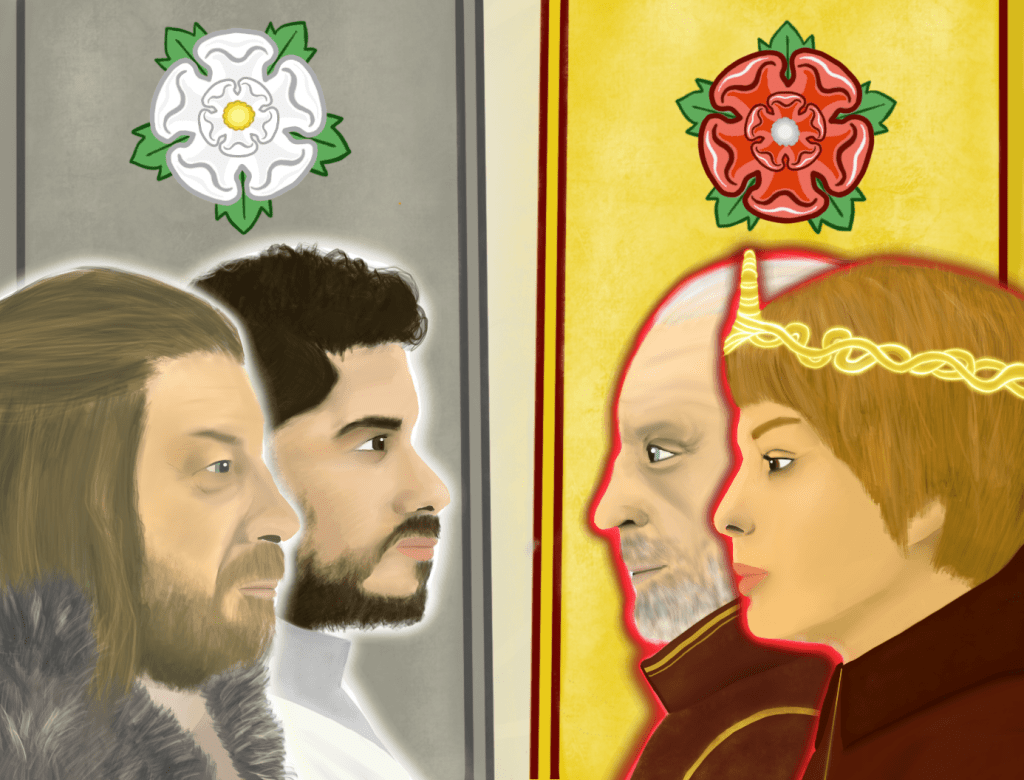

Perhaps the most famous fictional interpretation of the medieval period remains George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series, the literary foundation for Game of Thrones. It is overtly inspired by the Wars of the Roses, with the author citing the historical period to justify the violent, dark elements of his fictional universe. This continued cultural fascination with the era stems from the dramatic elements inherent in the historical conflict itself, characterised by revolts, bloodshed, murderous coups, and financial collapse between 1450 and 1500.

The concept of the ‘Tudor myth’, which framed the Wars of the Roses as an anarchic period marked by conflict, in the hope of promoting the idea of Tudor rule as one of civility and order, ultimately did much to encourage the rise and authority of the subsequent Tudor dynasty.

This mythography, traceable through chroniclers, Shakespeare’s history plays, and later the work of authors like Martin, served to diminish the conflict’s historical complexities. It achieved this by portraying historical figures, such as Richard III, as intrinsically evil. This technique transformed historical individuals into character tropes, which is what makes them so appealing to authors, who often forgo historical accuracy in pursuit of narrative effect.

This isn’t to say that Gregory falls victim to the ‘Tudor myth’, but her insistence on championing female agency through the use of supernatural power leads her to acknowledge the powerful influence that mythic simplifications have had on dramatic recreations, as seen in Shakespeare’s work. Supernatural allegations were yet another period-relevant myth used to discredit the rise of the Woodville women, and whilst Gregory chooses to use these allegations to reinforce the Woodvilles strategic initiative, it may at times be seen as a tool used to romanticise their ambition and discredit their struggle.

This specific appeal to dramatic narratives is reflected in the wider survey data collected by English Heritage. Although the Tudor era ranked fourth overall in popularity (9%) behind periods like the World Wars and the Roman/Victorian eras, its appeal is clearly defined. For female audiences, “romance and intrigue” were the top resonating factors, chosen by 54% of Tudor fans.

The Only Way is Woodville

Born in 1437 to Richard Woodville and Jacquetta of Luxembourg, Elizabeth Woodville descended from a lineage both illustrious and marred by accusations of witchcraft. Her mother, Jacquetta, was the eldest daughter of Peter I of Luxembourg, Count of Saint-Pol, and had scandalised the English court by secretly marrying the Woodville patriarch after the death of her first husband, the Duke of Bedford. The couple were fined £1000 for marrying without royal permission, though the marriage proved remarkably fruitful, producing fourteen children, including the future queen.

The Luxembourg family claimed descent through the mythical water goddess Melusina, a medieval version of an old pagan deity; a claim of ancestry that would later be weaponised against the Woodvilles. After her controversial marriage, Jacquetta became the second-most-powerful woman at the English court (ranking only behind Margaret of Anjou following her marriage to King Henry VI in 1455), a position which made her a prime target for such accusations.

The Woodville family’s Lancastrian affiliations initially positioned them on the losing side. Elizabeth Woodville first married Sir John Grey of Groby, who was killed fighting for Lancaster at the Second Battle of St. Albans in February 1461, leaving her a widow with two young sons.

Elizabeth’s fateful encounter with the newly crowned Yorkist king, Edward IV, occurred in early 1464. The King stopped near the Woodville home while travelling to suppress unrest in the north. When he attempted to make the beautiful widow his mistress, Elizabeth reportedly refused, holding out for marriage, a remarkable display of agency that may have been inspired by her faithfulness to the sanctity of marriage, or it may have been a ploy to encourage Edward to marry her. The secret marriage that followed was unprecedented: no King of England had ever married a subject before.

The Woodville siblings (now 12 in total) subsequently descended on court, requiring noble marriage arrangements. Between October 1464 and September 1466, the Queen’s sisters were married off in a rapid succession of politically advantageous matches. These strategic unions created widespread hostility among the established nobility, particularly the Nevilles, who saw the Woodvilles as ‘parvenus’ and displacing them in royal favour.

The witchcraft accusations against Jacquetta in 1469 emerged directly from this political hostility. Thomas Wake, a follower of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick (the “Kingmaker”), brought to Warwick Castle

The charges were clearly politically motivated, occurring when Warwick had temporarily deposed Edward IV and executed Jacquetta’s husband and son. Despite her vulnerable position, Jacquetta mounted a vigorous defence, evidence of her political prowess.

These accusations established a pattern of using witchcraft as a political weapon against the Woodville women. In 1483, Richard III’s parliament would claim that Elizabeth Woodville and her mother had used witchcraft to make Edward IV fall in love with Elizabeth, charges that resonated because they played into cultural anxieties around female power and the social upstarts who supposedly used magic to gain influence. The myth persisted, with later accounts fabricating sensational details: one chronicler described an incident at Elizabeth’s coronation where her Luxembourg kinsmen allegedly carried shields painted with Melusine to suggest witchcraft. This story appears to be a modern invention with no contemporary documentation.

Through strategic marriages and sheer political endurance, the Woodville family transformed from provincial gentry to the pinnacle of English society, though at the cost of enduring accusations that their success was achieved through supernatural means rather than legitimate political skill.

Illuminated miniature depicting the marriage of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, ‘Anciennes Chroniques d’Angleterre’ by Jean de Wavrin, 15th century

Gregory’s Interpretation: Secret Power and Romanticised Agency

Philippa Gregory consistently frames the Woodville women’s political ascent through the lens of supernatural agency, transforming historical accusations of witchcraft into displays of feminine power.

In The White Queen, Gregory explicitly connects Elizabeth Woodville’s influence to her legendary descent from Melusina, the water goddess, using this mythical lineage to explain the seemingly impossible series of coincidences that propelled a commoner to the throne.

Rather than attributing Elizabeth’s rise solely to political opportunism, Gregory dramatises her secret marriage to Edward IV as a triumph of love magic and female determination. The author acknowledges taking liberties with documented facts, filling gaps with explanations “of my own making,” such as Elizabeth drawing Edward’s dagger to defend her honour, a contemporary rumour Gregory chose to include in her re-telling.1

This approach grants Elizabeth Woodville romanticised agency, recasting her family’s ascendency not as mere ambition but as destiny, while acknowledging that the Woodvilles’ success came at the cost of enduring witchcraft accusations that discredited their political skill.

In The White Princess, Gregory extends this interpretive framework to Elizabeth of York, positioning her as the heroine who must navigate between maternal loyalty and marital duty. Capitalising on the much-loved ‘romantasy’ element prevalent in Tudor era retellings, as evidenced by the survey conducted by English Heritage. The novel amplifies the curse that Elizabeth and her mother cast on the presumed murderer of the York princes (a suspect list which included Elizabeth’s new husband, Henry VII), thereby complicating Elizabeth’s political loyalties.

Gregory’s Elizabeth of York is caught in a web of secret power; her mother, Elizabeth Woodville, masterminds plans for revenge by secretly supporting uprisings against Henry VII, forcing her daughter into a position of divided allegiance. The author explicitly labels the book “controversial” because her view of Henry Tudor was unusual, portraying him as a paranoid King constantly fighting off plots to overthrow him.2

The romanticised agency emerges through Elizabeth’s internal conflict, in which she remains in love with her uncle, Richard III (a contemporary propaganda tool Gregory choose to use in her work), even after she bears a male Tudor heir, creating a heroine whose personal feelings and divided loyalties subvert the agency and self-assuredness previously seen in Gregory’s depictions of Jacquetta and Elizabeth Woodville.

The television adaptations further emphasise this secret power through visual symbolism. The White Queen series features Jacquetta of Luxembourg explicitly performing rituals. At the same time, the 2017 adaptation of The White Princess sees Elizabeth of York well-equipped in the use of herbal medicine, going so far as to procure Mandrake during early pregnancy in an attempt to abort Henry VII’s heir. This creative liberty, which was criticised by reviewers such as Variety, underscores the difficulty of balancing Gregory’s romanticised vision with historical authenticity. Gregory herself defends this approach, arguing that the Plantagenet period offers far more than other areas of history, allowing her to advocate for previously neglected women’s stories.3

Gregory argues that she uses witchcraft accusations not as evidence of guilt but as proof that “powerful and effective women have been unkindly treated by historians”4. By embracing the contemporary anxieties that arose in the face of elevated female agency, Gregory attempts to construct a narrative where supernatural accusations become validations of political prowess.

Whereas Elizabeth Woodville is emboldened by her marriage to Edward IV in The White Queen. Her daughter’s experience in The White Princess is much different; whilst Elizabeth of York and Henry VII’s pragmatic marriage grows to be a union of authentic affection, she is constantly reminded that she is bound to a King, whom her mother believes was responsible for the murder of her two younger brothers.

Additionally, in the adaptation of Gregory’s novel The Spanish Princess, Elizabeth of York is haunted on her deathbed by this curse, underscoring Gregory’s framing of the Woodville women as paradoxical heroines. They are simultaneously powerful through their lineage and the powers they possess, yet powerless in the face of political manoeuvrings and the strength of their own abilities.

Jodie Comer as Elizabeth of York in The White Princess (2017)

The Legacy of the Woodville Women and The Historical Burden of the Best-Seller

Gregory’s interpretation of the rise of the Woodville women demonstrates how their historical ascent was both framed and undermined by narratives of supernatural influence. Their success, achieved through strategic marriages and political endurance, was overshadowed by accusations that their power stemmed from sorcery rather than legitimate political skill. These accusations, such as the 1469 charge against Jacquetta, were likely not based on concrete evidence of witchcraft but were instead used as a calculated political weapon. Such accusations resonated because they were a way to prevent the exponential rise of women, like Jacquetta, who were clearly politically attuned.

The long-term legacy of the Woodvilles is therefore inseparable from the concept of Tudor mythography, a framework that shaped interpretations of the Wars of the Roses. This mythography reduced the complexities surrounding the individuals involved in the conflict to mere character tropes, exemplified by the demonisation of Richard III and the portrayal of a scheming Elizabeth Woodville during Henry VII’s reign, which helped justify the rise, trustworthiness, and authority of the Tudor dynasty.

Gregory consistently frames the Woodville women’s rapid political rise through the lens of supernatural agency, transforming the historical accusations of witchcraft into empowering displays of feminine agency. By drawing on the mythical lineage connecting the family to the water goddess Melusina, Gregory recasts their achievements not as mere ambition but as fate, granting them a romanticised sense of agency.

However, this narrative strategy, which prioritises dramatised recreations of secret power and often favours “soapy reinterpretation” over historical detail, highlights the persistent tension between fiction and documentation. Ultimately, whether interpreted through the historical mythography that strengthened the Tudors’ claim or through modern fictional retellings that celebrate female agency, the experiences of these dynastic figures largely remain a by-product of dramatic necessity and enduring contemporary rumours.

Footnotes

- Philippa, Gregory. The White Queen. (Simon & Schuster UK, 2010) (p.314)

- Philippa, Gregory. The White Princess. (Simon & Schuster UK, 2015) (p 438) the

- Philippa, Gregory. The White Queen. (Simon & Schuster UK, 2010) (p. 322)

- IBID (p 324)

Bibliography

Conley, Kathleen. A War of Roses: An Examination of Tudor Mythography in Shakespeare’s First Tetralogy of History and George R.R. Martin’s, A Song of Ice and Fire Series. (UCLA, 2023) <https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8tz2h3gc> [26th November 2025]

Gregory, Philippa. The White Queen. (Simon & Schuster UK, 2010)

Gregory. Philippa. The White Princess. (Simon & Schuster UK, 2015)

Higginbotham, Susan. Jacquetta Woodville and Witchcraft by Susan Higginbotham. (2013) <https://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/jacquetta-woodville-and-witchcraft/> [26th November 2025]

Romans, Victorians and the World Wars top the list of the UK’s favourite eras, new research shows. (English heritage, 2024) <https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/about/search-news/favourite-eras-research-news/> [22nd November 2025]

Saraiya, Sonia. TV Review: ‘The White Princess’ on Starz. (Variety, 2017) <https://variety.com/2017/tv/reviews/white-princess-review-starz-jodie-comer-michelle-fairley-1202030398/> [20th November 2025]

Vineyard, Jennifer. Everything You Need to Know About The White Princess. (Elle, 2017) <https://www.elle.com/culture/movies-tv/news/a44381/the-white-princess-starz-guide/> [20th November 2025]

Recommended

Susan, Higginbotham. The Woodvilles: The Wars of the Roses and England’s Most Infamous Family. (The History Press, 2013)

Alison, Weir. Elizabeth of York: The Last White Rose: Tudor Rose. (Headline Review, 2023)

Hollman, Gemma. Royal Witches: From Joan of Navarre to Elizabeth Woodville. (The History Press, 2021)

Royal Bastards: Rise of the Tudors (Sky History, 2021)

Leave a comment